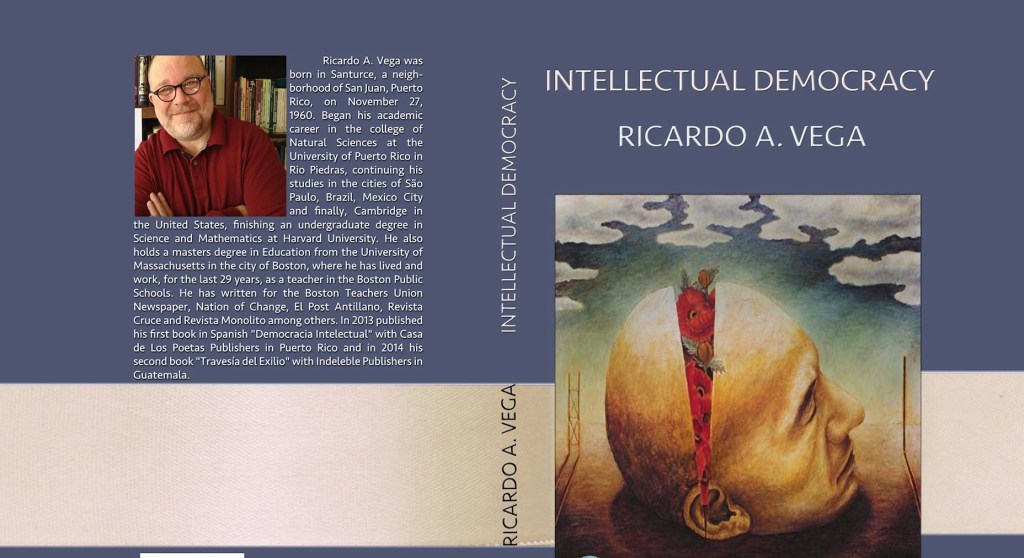

Cover Design: Judit Fernández Jiménez

Translation from Spanish: Nora Pasternak

Table of contents:

Coloring outside the lines

The Twilight of the Cemeteries

Notes for a Definition of Hell

Infusions of Heidi

Paralleled Shadows

Insular Youth

Childish Behaviors

Recovered Friendship

ReTURN

Forgetting the Establishment

Extended Metallic Auto Requiem

Precipices

Press Release

Celestial Pasture

Loves That Kill

Spherical Passions

Tiago

New Eyeglasses

Xenophanes’ Sun

Imagination

Master Oath

Treat(y)ing of Philosophy

Intellectual Democracy

Intellectual Democracy by Ricardo Vega: Or coloring outside the lines

Rubis Camacho

Intellectual Democracy, the text with which Ricardo Vega made his formal way into the world of literary publications, is a wonderful universe tinged with nostalgia, demands, existential questions, worldviews sculpted at a distance from a country that haunts him and also dwells in him. It is a loving compliment to a paternity bestowed on him later in life and which spreads tenderness to all things.

Therefore, when embarking in the adventure of reading these essays, stories and poems, the reader will experience their impact on the accustomed inner quest in search of self to which one surrenders when facing a text. In my case, my immediate desire was to write a letter to this Puerto Rican author who has lived in Boston for decades. Yes, the epistolary forms allow a certain intimate delight, which could well replace the warm embrace that distance withholds. It would be a bulky letter with questions, concerns and, above all, gratitude for the affirmation of a Puerto Rican community, which faces the Exile with wide eyes open and an inquisitive spirit.

Vega interrogates life, its mutability, with the mindset of a skilled intuitive, a maverick and a man who carries his roots in his memory recognizing the value of the inherited. So he moves genially in the genre of the essay; word whose etymological origin must be related to the Latin word exagium, which means weight, but a weight relative to the coins and metal used in them, that is, the gauge or value of a coin. Thus, the essay is valuable because the author’s opinion is calibrated in it. Ricardo Vega achieves, in the words of Ortega y Gasset, a dissertation of scientific nature that does not override the author’s subjectivity.

In the “Twilight of Cemeteries”, he fuels the concern with the mystery of death. The image of a human being facing a dead body permeates the dissertation. The author underscores the modern irreverence toward the bereavement rite and invites us to avert the emotional numbness “public death” imposes on us as a society. It’s a historical essay of overwhelming hermeneutics.

“Infusions of Heidi” exercises the unspeakable of pain. The author joins the suffering of Heidi J. Figueroa Sarriera, a cancer patient and friend. He communicates with the enemy who barracks in her body like in a wasteland. “So much love and such helplessness before death!” (Vallejo). However, like the poet, he discovers that solidary love is what gives meaning to suffering and vindication to death “Then all the men on Earth surrounded him; the sad dead body saw them, excited; he joined slowly, hugged the first man; and then, began to walk” (Vallejo).

The writer then directs his energies to “Recovered Friendship”, a critical analysis of “Treacherous Stories”, a bunch of stories I wrote in 2010 and as foretold by Puerto Rican writer Emilio del Carril, brought me great satisfactions, among them, the literary reunion with Ricardo. For obvious reasons I will not comment on the content of this book (the reader can judge my text), but I will do so as it pertains to the rigor of Vega’s analytic process. The author effectively builds his theory on the basis of my personal history “Then, it’s pretty obvious to me, when I read “Treacherous Stories” today, how these began to write themselves 35 years ago.” With enviable memory, he paints the religious scene, perhaps somewhat syncretistic, in which we develop a new spirituality in light of our camaraderie, encumbrances and individual approaches toward like-minded groups (it was a sweet and juicy time). He examines swiftly the front cover and each line of the stories, the language, the themes, the biblical references and points out my endless dialogue with the religious inconsistencies and my own. Vega investigates my ideological lines, selects favorite stories, and introduces story segments on his Facebook page. He plays as if a child who throws multicolor balloons into the air, leaving me, at the end, bare-naked on account of his accurate guesses… and thus he favors me with one of the most thorough and comprehensive works ever written about “Treacherous Stories.” Of course, the debt cannot be paid.

“Notes for a Definition of Hell” is an essay where Vega demonstrates the efficiency of “bad language,” He expounds it as an excellent tool of an autochthonous expressive power, also to be used when the text requires it and when in pursuit of a distinct effect. Humor offers nuances, it launches us into a strident world; it summons and deciphers us with an altered kind of aesthetics. In essence, he sheds light on the fact that “bad language” exists within the contexts of power and cuts without anesthesia.

“Insular Youth” and “Going Back” are essays-reviews of nostalgia and rescue of the Caribbean land. With the eyes of Jose Rodriguez, author of “Giant Footprints,” he brings us back the Carolina of olden days, with its popular characters and its beloved landscapes. Vega vibrates along with Rodriguez, enjoying and longing for the distant island.

The author’s analysis of our notion of children in his work “Childish Behaviors” is fully disquieting. The text pours out of the teacher’s eye, whose vocation is unremitting. He observes and understands his students parting from alternative viewpoints and challenges the systems that automate and nullify their natural curiosity. I imagine his eyes (so horizontal and oblique) contemplating, from a window or an aisle, the group of boisterous kids.

Several excellent stories appear in the book (“Paralleled Shadows,” “New Eyeglasses, “Spherical Passions,” “Loves that Kill,” “Celestial Pasture,” “Extended Metallic Auto Requiem” and “Press Release”). They stand out for their mastery of synthesis, a requirement of any good storyteller and, for the originality in the selection of the narrative voices. The element of intensity, about which Poe spoke, develops on each story until it triggers a stream of emotions. Isn’t it the fundamental task of art to move us emotionally? These stories are based on a painstakingly thought out language. Vega does not leave room for digression. He knows that the story is an arrow that, without deviation, must reach the target. The story “Paralleled Shadows,” is simultaneously hard and soft, inspired by the golden curls of his son, this is, from the depths of his soul. The stories run parallel in this narrative. I trembled reading “New Eyeglasses.” The reading of this an extraordinary text caused my sense of strength to falter. A burning library must be a traumatizing experience to witness, for those who could not face life without books. “Celestial Pasture” brought me special enjoyment. Two of its elements were very impressive: the recreation of the act of copulation on the countryside and the cow as protagonist narrating it with unmitigated rationality. In “Spherical Passions” Ricardo Vega practices the obsession for the object, symbol of the memory and of the stages of growth and life cycles. “Love that Kills” is a literary call for food sanity, the revision of Western habits and their consequent effects. The atonement of innocence pervades the narrative voice and teases the reader, until we understand its malevolent power. The Puerto Rican, in its oppression, waiting in the distance for the natural evolution to freedom for which all people should arrogate, is illustrated in “Extended Metallic Auto Requiem” and “Press Release.”

“Imagination,” “Treat(y)ing of Philosophy,” “Masterly Oath” and “Intellectual Democracy” are some of the poems that complete Ricardo Vega’s first book. The author disrupts the ordinary, transgresses, subverts and inverts orders and visions with utmost precision. “I grew up and during my first time of wearing uniform, saying nothing, sitting down and waiting for my turn, appeared out of thin air…”(Intellectual Democracy). The school is an essential part of his life and the inspiration for many of his poems and thoughts.

From his writing, this maestro looks outside the lines and invites us to prod strongly those who sleep. This book is not merely an aesthetic exercise, is the product of many years of thinking about life, many readings under a sky of self and others, vast exposures and countless surprises.

Go out into the world with the full force of those who believe that writing saves and transforms lives.

The Twilight of the Cemeteries

“Death, with its impeccable function of artisan of the sun, carves heroes, makes history and gives us a place to die in this land, for the future.”

-Eduardo Ramos, “His Name is People”

We not always buried our dead. Resembling a wild animal facing the lifeless body of another of the same species, we continued our journey without goal or concern other than food to satisfy our hunger. At some point, we stopped and if only for a few minutes, perhaps seconds, we changed in an instant. When we allowed room for the feeling that something was fading away with the inanimate body, a whiff, a tiny flash of a new consciousness emerged and our humanity found fertile ground.

We were not fully human yet. Still today, chimpanzees and leopards, as they persist on pushing their newly dead offspring with their snouts and paws, show us how they also since ancient times have felt the incredible and confusing loss of kin. However, we, on the way of becoming who we are, took a step further than other living beings when we began to bury our dead.

Although, we were only still Neanderthals, we already possessed the spark of the future. We moved slowly from indifference to the corpse, with tentative compassion, without quite managing to abandon it completely, for we retained the apathy and growing irreverence as a gift to the deaths of others. The appetite for understanding and interpreting death, developed during the original evolutionary steps of our upward slope remained and it became the forging force in the earliest civilizations. The Egyptians built their culture and society around that very concern. Their focus with the hereafter was the driving force that raised pyramids, justified pharaohs and prompted all citizens to ensure that their deceased relatives were properly prepared and buried with all necessary provisions and guiding elements for their final journey to the stars.

In their culture, the tomb raises to the zenith of its meaning and since then, we imitate, even if in a progressively degraded manner, the Egyptians invention. The practice of abandoning the body, with its assured exposed raw decomposition, became no longer conceivable and the conservation of the deceased’s body became essential. Even thousands of years and kilometers away, the Maya do the same. Their large pyramidal mausoleums were also reserved for the powerful, albeit, any Mayan family shared in the moral obligation to bury their kin, even if in the floor of their house.

Initial victims of a new human strategy, where a few seek ways to control the religious, political, military and economic elements of the pre-Columbian reigns to their advantage, the dispossessed would not allow their poverty to inhibit their proximity to the resting body. As time went by, they began designating a sepulchral spot in their limited residential space, moving the bones of the grandmother into a corner, making space for those of father. Even fetuses and children, who died very young, received the esteem and honor of being buried in exquisite vessels.

The advent of religious ritual and agriculture marked the arrival of the cemetery plot dedicated to the deceased, along with meeting points for those still among the living. These arrivals also cemented the ongoing tradition learned by preserving the memory of the departed. This is a legacy bequeathed to us by a community that irrevocably leaves its nomadic crossings, thus, bringing on the Neolithic Revolution. The current cyber revolution, with its divisive force, replacing the actual event for the virtual, threatens to complete the gradual abandonment of the burial ritual. This slow process started at the end of antiquity; it waives the active practice of preserving a memory grounded in an event with geographic permanence and aims to transform the protocol related to death and the disposition of the body’s remains, into an event belonging to the realm of the imagination. Today the knowledge of others’ deaths is instantaneous. This awareness is massive and far beyond the immediate family, which prods a diluted and ephemeral “like” on Facebook and allows us to continue with the other things we have to do. We proceed with our daily routine while simultaneously, intending to maintain and meet the required expression of sorrow the burial ritual demands.

The practice of cremating corpses against the increasing scarcity of land is a transitional exercise that exempts the grave. Appropriating the cemetery for ourselves, we rehearse a brief return to antiquity, this time placing the ashes in elegant urns, which complement the décor in the rooms of our homes. Modernity at its core, with its fervent repellence of morbidity, prevails and tends to usurp the taste for such practices, propelling the vast majority of people to spread corporal remains in the air over the sea or on any landscape, thought to be pleasing to the deceased.

A new ethic manifests itself. Human remains lost their place in the purlieu of families, cultivating the concurrently innovative and ancient conception that we return to the place from where we left. We got used to hear the Roman envoys for Christendom say dust you are and dust you shall become. Today, we pretend a greater sophistication and understanding, as we see ourselves as a group of atoms created in the stars continuing their journey of return and recycling. It would seem the Egyptians and the Maya are not as far from us as we had thought. Moreover, even without having become accustomed to the new way of disposing of our loved ones, it inherently places us in a trajectory of discarding the contemplative traditional death experience.

Nowadays, there is no time to reflect, even less time to cry and mourn human loss in lengthy lamentations. It is necessary to act quickly and carry on. Nor is there much time or space to gather the family; they are all away, scattered and above all, very busy. The ritual of death is remote and access to networks offering the family a convenient distant rite, also scales it up into a virtual wake in which all of us are offered the opportunity to become temporary family members of the departed. Fame ensuring a passage to the other world shared by hundreds of thousands through electronic monitors is not universal. It’s almost as if one, while living, must have cultivated a niche in the cultural imagination of a people that eventually will grow curious about the morbid details of their idols’ departure.

Common to our era are instant idols. The nature and circumstances surrounding their deaths acquire the right to an immediate funeral ritual and a virtual mass burial. This implies that the vast majority of deaths in the world occur in the most consummate anonymity. The bulk of humanity is thrown then into the mass grave of the inconsequential, also virtual. The faceless, those in the common pit, are swallowed and disappear with relative ease. Sometimes, we may experience hurt, get offended or feel enraged when we learn of the thousands of children dying in Africa caused by senseless and unnecessary hunger or other similar situations. Perhaps, we witness an instance where we see the hypocrisy of tears incited by the insane killing of children in our own backyard and particularly if they look like ours, but then again, those who die courtesy of our guns in the distance, appear to be more easily disposable.

What is this evolutionary path in which we have embarked by engaging in these new forms of goodbyes and dispatching those who are gone? Famous and anonymous deaths are displayed on the virtual scenario. Both are changing how we define and mold the world, who we are, who we will become, who we would like to be or pretend to be. Becoming instant relatives eliminates the possibility of knowing who the diseased really was. Our experiences did not include ever sharing a table, a classroom, a brother or a bed. Then we can but as quickly as possible, as required by the current cybernetic, create a fast sketch of the person who died and immediately develop an analysis, along with conclusions, perspectives and recommendations on how to proceed. All the former, based on what we establish supersonically.

These fast creations cannot but live within our schemes and interpretations of the world and therefore, have no choice but to respond to a personal agenda. This is the way we approach now, people’s death for the benefit of promoting our ideas, whether these are praiseworthy or not. It is impossible for us to treasure the memory of the events we shared with the deceased and that influenced our being; we did not know them. The new extended family built no tradition or continuity and, we are not responsible for the widows and children left behind or of guarding the survival of a specific lineage of thought that the deceased struggled to make clear and leave as legacy. The death of the other is now ours and we will use it as best as it suits us. There would be others that would take care of their loved ones, as a byproduct of our abandonment of the intimate ritual of burial and the quiet loss of the cemetery.

In this instantaneous reality, which abhors the act of allowing the required time for almost anything, mediocrity proliferates. The fast point of view dominates the landscape and everyone who has access to a keyboard or microphone hastily claims to have an innate wisdom, which, must be heard, applauded, shared and promoted. The abandonment of physically participating in the burial of our dead while appropriating the privilege of being part of his or her funeral, it’s a simple sign, among many, of the transformations currently affecting our sense of what it means to be human. Many old cemeteries are still preserved, but these mostly remain as monuments to the memory of who we once were and have little chance to be again. They are historical relics, even meeting points, but this time, for tourists.

The ancients attributed to Pythagoras and his followers, the introduction of the idea of reincarnation in pre-Socratic Greece. It was already known this was not their original concept. Tradition has Pythagoras travelling throughout Egypt, Babylon, Persia and possibly India, places where he learned all these notions, to introduce them later in Samos and Crotona. Pythagoras’ particular approach to mathematics and the central role that they play in nature’s mechanisms stemmed from what he learned in his travels. No mainstream scientist today takes the idea of reincarnation seriously. However, our modern mentality, based on the identification of patterns and laws, clearly answers to the Pythagorean heritage, which even inadvertently, is permeated by the idea that death is merely a transition between forms of existence. We never really die.

If public death is the new historical reality that is here to stay, we risk, with our frivolous and disrespectful way of addressing it, retreating into our prehistory and with a quick tap of paws and snout, announcing the continuous adherence to the new, yet primitive goal of satisfying the hunger of our immediate needs. The decline would be monumental. By cutting off the funeral event of its family ties, we dissolve the underlying meaning the diseased person’s name and face and now, publicly announced dead, had for the relatives. Therefore, it is in the persistence and recovery of what the deceased meant to loved ones, the activity and influential circles in which he or she participated and, in the avoidance of using said death with the purpose to speed up a given cause which we consider more important to advance, how we redeem our humanity. Thus, we would reemphasize the loss and recognize the piece of us, which departs with the deceased one. That memory must continue, for it personifies humanity itself and it is a crucial beginning for any project of peace and justice.

Notes for a Definition of Hell (el carajo)

Inspired by the open invitation to go to hell that Puerto Rican writer Graciela Rodriguez Martinó made on the digital magazine 80grados (http://www.80grados.net/2011/02/carajotour-2011/), I decided to write some notes on the history and nature of hell. Since, if we venture into the project to coordinate such a trip, we must know about which hell we’re talking.

The possibility of multiple hells is disturbing. Graciela herself admits the existence of numerous hells when without hesitation she sends to hell those who intellectualize the destination of her original invitation. The simplicity that Graciela uses as shield for her hell made me think twice about the wisdom of writing these notes. Since the other hell referred by Graciela, where I will end up for yielding to the temptation of this mental mas- turbation implies the rejection of those who go to hell in search of peace and spiritual rest. The other hell, that of the tormented ones with which nobody wants to deal, carries the curse and stigma that only the hell of hell can offer. Alas, we must not be surprised by those who think there is only one hell and apparent multiplicities are just variations of the same hell. In which case, like it or not, we all end up in hell anyways.

Hell resists definition. It is perhaps for this reason that Puerto Ricans accept it so easily. To the land that has transformed uncertainty into an art, hell offers a perfect plasticity to our daily discourse. Its deep historical roots have allowed it to evolve in tandem with our people and today, after centuries of collective carving, there is no Puerto Rican who does not know what hell is being talked about every time it is invoked. Explaining our varieties of hell to a neophyte, a foreigner or anyone who wants to understand the Puerto Rican soul, is almost impossible. Therefore, we rarely try to do so and instead, prefer to send them all to hell. We know it is precisely in these swearing to our foreign observer that lays any hope of understanding our national dilemma. In order to comprehend who we are, the confusion afforded by the supposed affront is crucial. Devoid of any possible framework, our analyzers only begin to understand by surrendering their minds into thinking about the native mess and wonder along with us, “What the hell is this?”

The geographical location of hell is also uncertain, as it seems to be both here and there. Although, we are continuously being sent to hell, occasionally we have to accept and acknowledge that this is hell. Either we go or we already live there. It is all contingent on the situation we want to categorize. Hell seems to have been the name the Spaniards from hell gave to the basket resting at the top of the mast of the ship. Intended as an observation post par excellence, was also the place where the movements of the ocean were felt more severely, tormenting the poor sailor whom the captain had sent to hell. It is not difficult to imagine how a good sent to hell in the midst of the fierce and unknown Atlantic would have spread fear among the members of any crew. Among those Spaniards, who sailed into the unknown, however, there had to be men of indomitable character and ready to face any vicissitude. For these brave people, one sent to hell would have not taken away their sleep, being able to survive the toughest storm. I dare speculate that, upon return to deck, the collective admiration of other sailors was crystallized as they commented on these men who were sent to hell. I like this story, even if it means a scandal to serious historians, whom can all go to hell, for the origin of hell as a positive thing worthy of praise. Since then, there has always been confusion among the uninitiated ones. Nonetheless, for those sailors who carried in their balls the semen of our Puerto Rican nature, there was never any doubt. Hell, hence, not is only synonymous of imitable heroism, but was also of an undesirable domicile.

It is said that in the nineteen sixties, while Luis Muñoz Marín was trying to introduce the party’s new leadership to the people during a public speech, his hands sought desperately for the piece of paper in his pockets that would assist his memory in accomplishing the task. A name as long and new as the one of the young and ambitious Rafael Hernández Colón, was not easy for the already and perhaps, less interested Muñoz. It is said also that after several scuffles between the contents of his pocket and his fingers, the loudspeakers boomed in the park, “Damn, to hell with it! Where is the fucking paper I’m looking for?” Sending to hell the historians’ opinion about the veracity of this story, for I had learned it from a dear and distinguished Social Studies professor as a 19 year old student at the University of Puerto Rico, I imagined the hero, without making the slightest attempt to apologize while cheered by the masses who heard in his abrupt words the strength of character they sensed lacking in the future leadership. This recalcitrant Puerto Rican nature gives us a niche in the perennial battle of the continent and echoes the voice of Hugo Chavez when he reaffirmed, also in a speech to the masses, “Fucking yanks, go to hell hundreds of times!” Again, Hell is which unites and stamps, with its rich meaning, the value of our heritage, the same hell that, according to Louis Peru de Lacroix in his “Journal of Bucaramanga,” was continuously blooming on the lips of Simón Bolívar. This is itself the very hell, which North Americans, deflate of its power and content with their pathological euphemism of “ay caramba!” The latter, place in the mouth of the Latino character from The Simpsons, is the hell full of endurance, challenge and presence of Muñoz, Chavez and Bolívar and of all those that from Cuba tell them to go home, namely hell, with their versions of what we are.

Many may think that these notes are Hell or, what the hell is happening with Ricardo; he probably has nothing better to do. What the hell do they want? After 26 years in exile, it has been Graciela’s invitation that helped me recover and understand the ambiguous depth to which I belong, in this vicarious representation of hell. I exorcise myself to hell and of any attempt to encase my heritage in a rational fashion and I leave to the politicians on duty, the fruitless project of explaining whom we are and to try to impose what they think as the only way forward. To hell with these people! They do not understand that it is in the axiomatic mixture of hell where our race flourishes. It is in this wonderful flexibility, which has taken us centuries to perfect, that we are ready to deal and produce art, culture and beauty with whatever is thrown at us. Making no effort to deny the fight against injustice and stupidity of our country, thinking how we think and being whom we are is good as hell. Therefore, leaving our philosophical entity in order to pursue predefined ideals, sounds to me boring as hell.

There has never been any great Puerto Rican thinker who has not found inspiration in our inscrutable madness, in our almost impervious turmoil of contradictions. Betances, frustrated by the lack of enthusiasm that the Islanders were showing in the fight for independence, laments at the end of his life, “What’s wrong with Puerto Ricans that they do not rebel?” This phrase, to be sure, must be the sanitized version officially adopted by history. What Betances like any true Puerto Rican, definitely said was, “What the hell is happening to Puerto Ricans that they do not rebel?” This reflects the anguish of allowing oneself to be ambushed by the notion of a predefined path for Puerto Rico. It is clear that both old and new Puerto Ricans don’t give a hell about defining themselves. Why is that so? Because it is with this uncertainty, our constant companion, that we have created our best literature, painted our best paintings, produced our best theater and most of all, fine-tuned a language with so many levels of possible interpretation that other Spanish speakers who hear us, do not understand what the hell we are talking about.

When the First Hell Tour leaves from Ponce on the 29th of February, it will be part of a long tradition that if we are lucky, will be preserved for our children to enjoy. This group of 20 intrepid Puerto Ricans is carrying on their shoulders the plethoric responsibility of prospects that our Puerto Rico deserves. May these brothers and sisters be blessed, the latest from a long lineage of a people with the most incongruous contradictions, unafraid of neither sending nor going to hell. To you, my compatriots, who are truly hell, thanks for making me understand and rejoice in being part of a people who are all crazy as hell.

Infusions of Heidi

War, producer of immeasurable pain, slaps us with its foolishness while making us feel powerless to stop it. Foreign wars inflict pain one experiences only intellectually. The anguish one feels for the unjustified victims of its brutality seem to be inversely proportional to the geographical distance where the conflict develops. That is, the further away one is from the suffering the less one is affected.

The printed or electronic images and words are catalysts that stimulate reflection and apparent natural feelings of compassion for victims of war, along with repudiation for those we deem responsible. Although we are not personally witnessing the conflict, our love and appreciation of life, demand our condemnation of the purported rationale for this or that war. However, after playing our accusatory role from afar, we continue living our lives, keeping at bay any distant suffering and anxiety from intruding in them.

It is always possible for fear to linger, particularly after reading and hearing the testimonies of those who have lived the horror of war, wondering how it would have been for us to have the bad fortune of experiencing this pain ourselves. We imagine, though never with complete clarity, a scenario where we, along with family and friends, would live the anguish and confusion of such suffering. Then we ask ourselves, puzzled, what will happen next. However, even this concern is imagined as distant and therefore, temporary.

Battles are flooded with pain and uncertainty and have many forms. It was reading the book “Infusions” by Heidi J. Figueroa Sarriera (“Infusiones/Infusions”, edición bilingüe/bilingual Edition, 2011, ISBN-10 0615392644), which brought such confusion to the personal scenario of the here and now. Telling me about her struggle against cancer, Heidi, as a friend, had extracted the “abstract” quality of the notion of war; she underscored the pain by incontrovertibly confronting me with it, thus, making it very real. It is no longer a stranger who suffers. Consequently, I am unable to continue my life with its daily routine as usual, with a subordinate knowledge of distant pain. Are the pain, anguish and uncertainty of a close friend, what envelops my soul and fills me up with an apprehension I cannot easily circumvent?

The overwhelming monster of war leaves many victims on its path and except for rare occasions, I don’t care nor entertain thoughts about the soldiers who died on both sides of the conflict. My disconcerting suffering is normally reserved for those who have no control over the fate imposed on them by the political elite. It is in this lack of control where the anguish of the victims takes root, where their attempts are futile, where everything that happens is determined exogenously and the enemy imposes the circumstances. In the terrifying battle with cancer, where the enemy lives within us, Heidi explains, the corrosion is experienced as an outshoot from the very core.

However, the necessary transformations imposed on the skin, tongue and hair, owe their distortions not only to the illness, but also to the medical-pharmaceutical complex that, with its curative strategy, promotes them. Humans and laboratory mice then participate in an unpredictable evolutionary reunion of industry and science where these combine to eliminate all vestiges of self-control. Abandoned as victims of war, trapped among unknown hosts and left to the mercy of an arbitration to which one has not been invited, we become a sacrificial offering that ensures the continuity of an alien and senseless paradigm.

As if this were not enough, body and mind seem to be separated when our “piece of meat with eyes”, as Heidi calls it, decides to act out its idiosyncrasies and reacts to chemotherapy in ways that doctors cannot predict. This corporal torment adds a third character to the table where our fate is decided. The pain that shakes us so hard and agitates our senses to recognize its undeniable presence still holds a new dirty trick, mocking us with the impossibility of naming it. Heidi conveys unequivocally that the words “pain” or “pains” are inadequate to describe the range of intense suffering to which cancer and its treatment submit a human being. Pain is then that “another who cannot be named” and threatens to claim the fourth chair in the grotesque congress of power controlling the threads to which our lives seem to be tied.

Not satisfied with the “meanness” of language to put it in its corresponding categories, pain ensures to ally with the bacteria that take advantage of a weakened immune system, in order to fill the tongue with mouth ulcers, transforming speech into a torment. There is no language to describe it accurately, but if there were and our minds were able to find or imagine it, in a creative act that unmasks the pain, naming it would inflict an even deeper torture. It would seem macabre, like a spiraling whirlwind enveloping us and sinking us into a bottomless hole of anguish.

Forced to subject the body to robotics, Heidi explains how, from the womb, we are measured and analyzed by machines and in the first months of life, our immune system is reprogrammed with vaccines. Pacemakers, prostheses, etc., take the modern man towards a hybrid robot, an event she experienced directly with the medport, a permanent medical device that allows regular injections of chemotherapy.

Survival drives us to make a pact with the machine, as it gradually integrates itself into our body with its devices and leads us to the limits of the human frontier, leaving us wondering who or what we have become. The tragedy of the disease is now perceived as the mechanism that accelerates an evolutionary path and mysteriously jiggles our notions of what it means to be human.

On the edge between life and death, with eyes trying to help a strange and unfamiliar touch, measuring the meeting points between oneself and the surrounding world, dragging a skeleton taken and arrested by the stimulation of producing white blood cells and, fingertips with autonomous sensations that make the mundane task of buttoning up a blouse a real feat, there is nothing else to do but wonder if there is a way out; a ray of hope at the end of this devastating ordeal.

At that juncture, the present is discovered as a source of interest and focus of our efforts in the pursuit of happiness. In the acknowledgments and introduction preceding the text, Heidi asserts that it is friendship what makes pain personal for the observer and gives comfort to the person who suffers when being surrounded by people.

Knowing that we are loved, gives us strength and a vigorous reason to cling to life. The circle of friendship is then completed, granting real understanding and meaning to existence. If we are and want to remain being, is due to the relationships we have with our loved ones.

It is the love and friendship that we share with them, what we are terrified to lose.

Paralleled Shadows

I was watching my son clapping his tiny but already defined hands as if rehearsing for some future applause. Those hands that a few months ago my child discovered, unexpectedly and shocked, as if a hidden angel had added them to his arms while he slept or while he looked mesmerized at his mother. Those hands now explore and take, with an insatiable curiosity, everything he sees. Already sitting, but with a small swing that still keeps me and his mother in a constant state of alert, I noticed, as the light of our early-morning window was transforming his curls into golden swirls; how the silhouette of his shadow was expanding on the Bostonian polished wooden floor. I was thinking that this could be that other child. The one who, arises in my mind, when I rejoice in my son’s happiness and acts, as counterweight to my delight. That other child who, without having the constant pampering that my son enjoys, would grow isolated with fear and distrust for everyone and everything around him.

I decide, though with trepidation, to accept the dubious invitation and walk on routes and places that, as everyone, I would rather pretend do not exist. The windows of my apartment were wrapping the skyscrapers of my city in a gentle drizzle that was cooling the atmosphere. Even so, I was roaming; feeling the arid gusts of dry wind coming from the Somali peninsula. The smell of uncollected lunch leftovers still on the table punished my neck, while the remaining shreds of muscle on the living skeleton barely retained a scarce memory of his last meal. I tried to communicate; he did not speak. Strenuously, while his mother shooed away hovering insects, he opened his infected eyes. I later realized that for the last time and without words, the depths of his jet-black pupils were inviting me to enter a second door. I agreed. In those eyes, I looked into a valley with other 22,000 children who, by name, were bearing today’s date. Horrified, I wanted to escape the trance, since I knew that these would be added to the 22,000 children of yesterday that along with the 22,000 of the day before yesterday and this morning, were forming an immense chain of needless deaths that would drive me to the brink of insanity.

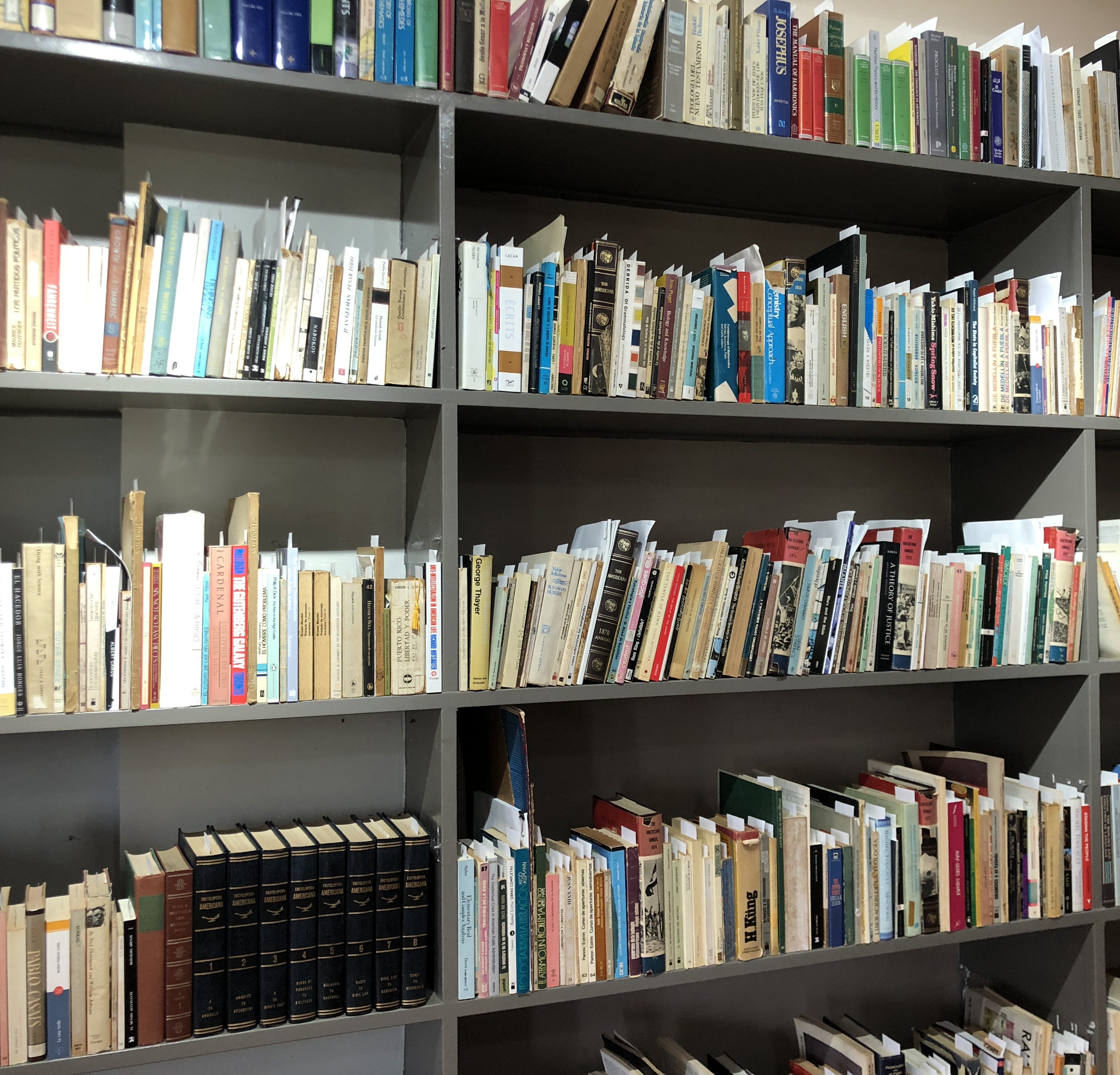

Upon returning, I went to see my child. He was practicing crawling on the floor of my library and, with a twinkle in his eyes, was trying to reach books off the shelves that were within his reach. This was one of our daily rituals. Depending on which bookshelf he decided to explore I would say to him, “this is the section of mathematics” or “this is the philosophy one, literature, science” and that’s how I continuously guide him towards the dream that will be his future fascination, when he impatiently tries to read the books that I read. Like any parent, I imagine my son going through all my ways intellectually and clearly understanding his heritage. I see him with a bright mind well equipped to discover his role in life.

Abandoning the magnetic appeal of the spines of my books and returning to the floor and his crawling, my son, with his emerging idea of what a book is, opens his children text of colors, where he gradually learns to identify the giraffe, the lion, the bear, the flower, the letters and all the fascinating world of wisdom and knowledge that encloses the written word.

Moving away from the window, his shadow disappeared and with it, at least momentarily, all the infant souls who would never have the opportunity to be educated and to contribute, with self-understanding, to a better future. But time did not stop and, with sadistic cruelty, the clock on the wall marked the seconds, in fours, announcing the interval the world takes to dispose of each child’s soul; over 8 million a year.

It is impossible to predict accurately the future of my son. His life will be like a ladder where each rung will be marked by future memories. He will only remember his first steps by looking at the pictures that his mom and I will show him. But consciously endorsing the memories of his first day at school, his first kiss, his first time reading, the first understanding of what he is, his graduations, his wife, his children and grandchildren, he will also understand how these will live paralleled to his shadow. That shadow that his father saw on a rainy day on a Boston summer.

Insular Youth

José Rodríguez and I met toward the end of his 31-years career as a teacher in the Boston Public Schools. He was always very quiet; living in his own world. I remember the day someone asked his name and he replied, “Rafael Hernández Colón.” I did not think anybody around him at the time understood the historical reference. Only I, silently, kept watching him while trying to decipher the meaning of his answer. Although I knew who Rafael Hernández Colón was, I wasn’t sure of José’s intention when appropriating his name. However, what did not escape me was the mischievous smile he displayed as he said it. I suspected then, that this was not a statement of party loyalties, but rather a trap, a nearly insoluble conundrum addressed to the Americans around him. In that instant, I realized that my life as an improbable graft in the American Northeast had already been lived by others. José had already been carrying it tied to his back for many decades. The feeling of being part of something and yet, belonging to another world which few know or understand even less. I now recognize when reading his short story “The Man He Carry Uphill” the weight of the Island’s frozen memory tied to his back, while agonizing and starving by a famine of new memories, enduring the insufferable passage of time and the difficulty of sharing the experience which, while im- possible to untie, unveils the story. A tale of two characters unfolds where unexpected and incomprehensible changes feed doubt and transform a tied knit friendship full of illusions into an inescapable curse. The story bears similarity to our exiles enticed by their sirens’ songs that eventually transform their future dreams and feats into delusions difficult to release.

Exploring a narrative that seems to act as an extensive exorcism of internal concerns, José uses his memories of childhood and youth in Puerto Rico, as the context where all the stories in his first book (“Huellas de Gigantes” Xlibris, 2010, ISBN: 978-1-4568-1766-4) take place. Son of Carolina, known as the town of the giants, José elaborates in detail the deep marks left by the gigantic respective characters of his childhood and adolescence in the island. These are the ones who, decades later, he uses for self-exploration and reflection. Despite having lived most of his life in Boston, the experiences of this city seem to play no role in such introspection. It’s as if everything stopped and decades of living abroad dwelled suspended in a sphere where time neither passes nor makes any apparent impression and, where he constantly explores who he was, in order to understand who he is. However, José surprisingly avoids in these stories, the classical longing for a life in a bucolic and idealized landscape and alternately, places the human relations of the town’s characters at the front and center of his thinking.

In a faithful representation of our almost impenetrable Spanish language, a flood of native phrases adorns the stories. Between “the bayú” and “the mangó bajito”, the “jolglorio” and “sal’pa fuera”, the “chavienda” and the “titingó” the foreign reader will suffer severe headaches trying to decipher the Puerto Rican verbiage. For those born and raised in the island, like José, there is no such a problem of interpretation. On the contrary, it’s on this regional phraseology, where José authenticates himself and invites those who share his experience to revive it along with him.

However, the physical return to the island is not an option, José confesses privately. Except for occasional visits that due to their temporary nature can be enjoyed to the fullest, the possibility of living on the island permanently has become an unthinkable adventure. Puerto Rico nowadays is a country where the moral debacle that fuels rampant criminality deems human life an easily disposable object. In his book, José endows us with another land. In his stories, we see a nation of artists on the brink of apparent madness, caused by the creative clarity that portraits and transforms the town and its inhabitants with burning brushes. There are vagabonds with violent and unknown schizophrenias that, with alternate tenderness, caress others that are marginalized, and in turn, receive the understanding and acceptance of the community. Forests and mountains that feed and grow with the ancestral spirit of Taína princesses; magical embroidery producers that in ecological metaphor eliminate the disease and torment of those who on their medicinal leaves and stems, find refuge and then, return the maladies to those who foolishly go away. Fabled dogs and cattle that surprise humans with their mutual understanding, know-it-all villagers who by pretending to be governmental bureaucrats, complete a microcosm representative of the national absurd reality where good is bad, positive change is misunderstood, should be restricted and, if at all possible, eliminated. However, José does not describe them with- in a town that becomes defensive and discourages the return. On the contrary, it is in the nostalgia of the innocent years, by reflecting on who we are that our motherland acquires meaning. Our memories of those characters are then a perennial invitation to return, even if only mentally.

A town with its square, streets, corners and the collection of characters roaming it, can summon a certain longing. In perfect harmony with one of our strongest Caribbean traditions, José assigns nick- names to all sons of neighbors in the town as a descriptive feature. Thus, without paying attention to the real name of any of his characters, José takes us by the hand and examines in detail the idiosyncrasies of Bulova, Paleta, Tirijala, Pan de Mallorca, Comegofio, Brocoli, Bien Me Veo and many others that circumnavigate his stories. With keen eye, José minutely examines his actors in a combination of child-teenager that kept these memories like treasures and that, now as an adult, analyzes them in such vivid detail that it seems as if they occurred only a few days ago. The endless discussions of the new generation in the town center, of which José was part, intended to provide the final analysis of each pondered situation but, simultaneously, recognized and honored the heritage and legacy left by its elders. The old guard’s influence with its circle of endless debate, had solved all discussions, the problems of the local folks and therefore, also those of the country. Moreover, the previous generation had bestowed the new one with the knowledge of what they are or were. Even José’s naughty teenage, inciting his buddies to be chased by the neighborhood’s lesser guard around the town square, after the mild torment, integrates a tone of respect towards the elders. For, at the end of the frolicking, the boys make sure to pay tribute with the required reverence to the character, making of this mischief a healthy adventure that quenches the thirst for laughter, but holds its proper place within the social strata of the town.

From abroad, we do not know whether the Puerto Rico of José still exists. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t. If it still lives, it must be hiding under the cloak of confusion and desperation that is the Puerto Rico of today. Maybe the small groups, bright spots, are where our goodness is manifested and where at the same time, the peaceful feeling of being protected by neighbors and cohabitants from the town, district, neighborhood, village and the urban enclave still shape the lives of future generations. Longing per se is not the paradigm I want to use for what the present Puerto Rico should be- come. If José doesn’t do it in his book, why should I? He rather teaches us that it is wiser to remember what we were, to understand who we are. José’s memory goes back to those days where adults were respected, admired, observed with amazement and emulated. Those values along with an overt passion for learning were still a fundamental part of the consciousness of a young Puerto Rican. Perhaps the crisis in the Puerto Rico of today and of many of the countries in similar predicament is precisely there, in the lack of humility towards the preceding generation. To think when we are young that we know everything may be natural. Nonetheless, casting aside the wisdom of those who have already lived might be the lynchpin of our debacle. José unequivocally asserts that neither radio nor television molded his character and that the actors from his small-town drama are responsible for the deed.

As a teacher in the United States, as was José for more than three decades, where many of my students know everything when in reality they know nothing, I dare say we are living in a new experiment in human evolution, a society where young people look towards their peers in search for inspiration and answers. Misleading themselves with mediocre responses, they waste the opportunity to get educated, therefore, guaranteeing another generation subjected to the abusive whims of a few. It is then that as an adult, José invites us to think and live, reviving, another type of youth. A youth that, as in his story “The Competition”, faces the challenges of its small business enterprise with wisdom and without violent confrontations; the nostalgic youth.

José ends his book suitably, by opening a masterful window to what we were, with verses from the Nica that also understood, in his adult years, the value of early life.

“Youth, divine treasure, that goes away to never return. When I want to cry I cannot and sometimes I cry without wanting to…”

Childish Behaviors

“When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child, but when I grew up, I put aside these childish things”

Paul, 1 Corinthians 13:11

There is no adult who has not been stunned by the honesty of a child. Children, either with their gestures and facial expressions as newborns or with the impertinent simplicity of their questions and observations when they grow older, slap with sweet cruelty the deceptive nature of the adult world, constantly forcing us to reconsider the society we have constructed and what we offer them as a future. The presence of a child requires the adult to react, to take a stand, either worship or resent, but impartiality seems to be forbidden in such situations. It is impossible to sit next to a child and legitimately continue as if nothing is happening, because even pretending to ignore it is just a failed attempt that requires effort and that is also transparently revealed on our faces and by our gestures.

Childhood was not always recognized as such and, it seems that it was not so until the late Middle Ages that it began to be appreciated timidly at first, as a special stage in the life of a human. Until then, except on rare occasions, children were seen and treated, simply as small adults (Ariés Philippe, 1962, “Centuries of Childhood, A Social History of Family Life”. New York, Alfred A. Knopf). Clearly, such a transition has shown progress, it has instilled in many the outrage in response to the abuse present in the use of children for labor and military tasks, besides providing some protection against possible physical abuse from parents and relatives. Notwithstanding, we’ve also lost something when creating the category of children, since they have been deprived of the right to be heard with the due legitimate attention and respect effortlessly granted to an adult. The metaphor of maturation is then introduced into our culture, turning the thoughts and actions of the child into childish behaviors that eventually must be overcome.

Children are born with a natural beauty that moves us from the outset to love and protect them. Being devoid of such feeling, suggests something wrong with the adult. This irresistible beauty can easily be seen as an evolutionary strategy that attracts the essential care that ensures survival. Otherwise, we would speedily perish. A human at birth is among the most defenseless species of the animal kingdom. Unlike horses, elephants, snakes and other tens of thousands of animals, we lack the slightest capacity to ambulate, much less provide food independently in case of abandonment at birth. Except for the beauty we show when we first open our eyes, we only have crying as a tool for communication. The latter is not so detached from sweetness as it would seem at first, since when heard, the people responsible for assuring the newborn’s survival, brokenhearted, run to soothe the baby receiving as their only reward the satisfaction caused by the thought of being needed by a child. How such incapacity at the beginning of our lives has the power to compel so much help, still remains a mystery of nature. Even so, since during adulthood, such a strategy is intended to work only rarely, in a grown up world that seems to find justifiable reasons to despise and abandon the needy. The adult loses almost every right to disability. It is a burden for society, which seeks, sometimes behind closed doors and others with public displays of arrogance, to get rid of such “weight” expediently. The adult world requires the ability for self-sufficiency and the selfless aid we give to children, officially seems to conclude with the end of childhood. From then on, the education that the adult feels responsible to provide to the adolescents constantly makes clear that they must begin, as soon as possible, to look after themselves.

As a teacher of children who are between the ages of 11 and 14, there is something that is relatively easy to notice. The vast majority does not like attending classes. For years, I have interpreted this situation as an act of immaturity, a desperate, but futile attempt to hang on to a childhood that should be once and for all abandoned. Lately, after becoming a father, I have radically changed my position. I have confirmed with my own children how a child is born with an uncontrollable thirst for understanding the universe around him. The world for them is a huge classroom of which they never seem to get tired. First, adults get tired of constantly having to feed the children’s curiosity since they always want to know more. However, once the school enters the life of a child, learning becomes a duty and that freedom which we previously had when exploring as passion guided us, vanishes early in the classroom.

Children offer us the possibility of a pure, free of hidden agendas relationship. They teach us that even when depending entirely on others, humans can completely offer themselves, risking everything, without the slightest questioning. The rejection of the adult is therefore the door that gives child’s entry into the grown-up world. It is always an adult’s action what introduces doubt, never an act of the child. The reality of the adolescent is the sort of a trauma where he is trapped between the forced abandonment of child- hood and the reluctant acceptance of the adult world. The teenage rebellion becomes a desperate attempt to a personal and social revolution that by being besieged by two worlds, one in which little or no theoretical justification for action was required and another, where the judgment of courage and intention is constant. This makes a firm ideological foundation extremely difficult to attain. Teenagers then act on instinct, making them, in the eyes of the adult who has devoted years of polishing reasons, an easy prey.

Adults simply dismiss this rebellion declaring it a stage, and as such, temporary.

II

“Let the children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.”

Matthew 19:14

Children are the ultimate instruments for measuring our patience. There is no quick solution when dealing with children. The attention they demand also demands time. Any attempt on our part to accelerate the process will inevitably invite a flood of frustration for the adult which, to worsen the mood, might even bring laughter to the kid. It is as if children estimate the value of the care they are given in proportion with the lack of hurry that we show. That’s how children question, with the imposed clause of total and extended care, the haste of the present. Visits of momentary affection have no place in the children’s hearts. The human relationship they offer as alternative, either is deep and enduring or is not at all. Repetition also appears to play a key role in the lives of children. Once they discover a game, book or favorite television channel, they tend to play it, read it or see it, repeatedly, depending on the activity. It is as if calm is discovered and experienced in a kind of mantra, a ritualistic activity that looks for real connection, understanding and full enjoyment of what is observed and so again, in stark contrast to the fast world of flickering attention of the current adult world.

Disappointed by the condition of our nowadays world and in constant search for improvement, we adults are confused by our lack of progress towards happiness, our inability to build consensus and the disastrous absence of any possible historical reference that would clearly point the way. Faced with such a debacle, I dare propose a second look at the world of children and try to see in it and in the way they are, a possible message. The behavior of newborns, even including their first years of life, depends very little on what they have learned and observed since they just began to live. The fact that there is such behavior must be the result of millions of years of interaction with the environment, development and adaptation to the organisms with which the child meets when born. The final decisions, of which behavior to express or at least those we see currently, should represent the best possible alternatives and those that largely increase the chances for survival. Something that is the result of such a long process of adaptation should be observed, studied and appreciated, as a solid education that nature offers us of how to do things, so its outcome is the most harmonious state between us and everything that surrounds us.

All our revolutions and political changes efforts seek, if one thinks about it, to equal the world of children. A world of peace, happiness, almost total lack of concern, joy, play, unconditional love and complete trust in the goodness of those around us.

Utopia? For us, perhaps, but for our children, it is the only reality they know.

Recovered Friendship

“In the beginning was the Word…” John 1:1

All of us were Pentecostals.

We thought that was precisely how it ought to be. According to us, only in revivalist churches the Holy Spirit manifested itself with clarity, which to us signaled that we were correct and that were truly Christian. The Catholic Church was excluded totally from this scenario. We exhibited a Protestantism learned, who knows how, that allowed us to look with condescending and suspicious eyes other Christians who still even when congregating themselves out of the Roman bosom, did not live fully the manifestations of the Holy Spirit. The Presbyterians were the worst, almost Catholics. The Methodists were quite cold, which I learned later, as a historical justification of my unfledged analysis, that they had dangerously distanced themselves from the original revivalism and that they ought to seek within their roots the return to the right path. Then, there were the Disciples of Christ, a difficult group to place within our paradigm of salvation, for even though their use of the Word was identical to ours, not all the congregations showed the fire of the Spirit that sealed and eliminated any doubts about redemption. It was in this last world, that at the time we thought as inundated in ambivalent redemption, where Rubis ambulated.

Having graduated a year before I had, we were never in High School at the same time, given that during my senior year and that of my conversation, she was a freshman at university. Many walks on steep hills that pointed the way to her house were ones that nurtured memories of our brief friendship. At the top of the hills of Guaynabo, in the tiny balcony that allowed the breeze to envelop our conversations, we went from school in pilgrimage, to Rubis’ house to share with her the lasts events at the Margarita Janer School and in our Confraternidad de Estudiantes Cristianos, “la Confra”, the name by which we all knew it. She was one of the designated seniors of the group, title that we gave to an ex confraternos who had graduated and for the leadership that had demonstrated in high school. They continued as our advisory group on spiritual issues, which in those days covered all topics. Their approval, comment, advice and finally, their very word were trophies anxiously sought out. Next to her house, over other hill of Guaynabo, was the temple of the Disciples of Christ, to which Rubis belonged. I only have threads of memories about the one and only time I participated in Rubis’ church. What I preserve recorded in my mind is her image as she walked to the minor pulpit to read a portion of the scriptures. She walked speedily although displaying a regal, self-possessed presence. Her poise was distinct since her early youth and thus, commanded the respect of the entire congregation.

Seated at the balcony, where anyone who would come to Rubis’ house was welcome, one could see clearly the family room through the main door that, obviously, was left widely open. I inspected the furniture with the corner of my eyes, but concentrated more on the bookshelves that looked like Rubis’, library. There were perhaps four of five shelves, as adolescents back then, they represented a healthy number of books read. A brother of the Confra mentioned to Rubis my last sermon at school and, how I presented a distinction between the imperfect search of humankind for the divine and the incarnation of Jesus Christ as the divine form personified seeking out humankind. Rubis’ praises about my initial homilies impacted me greatly and I still protect and treasure them as a grateful student who recognizes the precious mark of his mentor in his life. Nevertheless, as a preview of our future intellectual careers, shortly after Neruda scratched the surface of the exchanged biblical references of our discussions, there was an egregious partition in our conversations. My contribution consisted of freshly read passages from memory from his autobiography “Confieso Que He Vivido”. Rubis gravitated more towards Neruda’s poetry and, in one of those comments is where now I see clearly, the origin of the sensual passionate tone of the “Cuentos Traidores”. It launches a synopsis of the poem 1 of the “Veinte Poemas de Amor y una Canción Desesperada” and while citing the Chilean bard as he describes hurrying to touch, the pubis of his beloved maiden as damp musk, she openly divulges her arousal as exemplified by the goose bumps on her arms. That was the last time I saw Rubis in person.

At the same time, there were sweet memories of the current protagonists of our literature in the making. Within their own universe and though parallel to ours, Rafael Acevedo and Leo Cabranes, also roamed the hallways of the Margarita Janer School, already selecting the adjectives for the verses of their future poetry books.

“The precise word…” Silvio Rodriguez

It is evident when I read “Cuentos Traidores” today, how these started to be written 35 years ago. However, the quality Rubis has cultivated in her narrative, during more than three decades, goes beyond anything I could describe or exalt. The indisputable intense labor that she places in each of her sentences, her acute sense of the imperative of keeping a captive reader and the use she makes of the power of the written word to achieve such objective, possesses a unique quality. Imagination, that incessant producer of new worlds, is present in each story and nurtures the certitude of that which until that moment was the best work of all. Then, she would invariably surprise me with the brilliancy, inventiveness and other unimaginable crevices through which I was to be taken to the next story. Who except Rubis has the ingenious fertility of placing a regurgitating whale making an entrance through what seems to be San Juan Harbor? Not just any whale, for this would be relatively easy. It has to be then, for the enjoyment of the enthusiastic reader, the whale that swallowed Jonah. Tempting immortality in the Puerto Rican literature through her stories, Rubis places a redeemed Don Pedro Albizu Campos as witness to such incredible disembarkation. Don Pedro, who has not slept for 3 days while in the dungeons of El Morro and, in one Sunday morning, resurrected, ends up giving specific instructions of how to proceed to our own most recent and unexpected visitor. Soft and seductive, the cover of the book, by Puerto Rican painter Susana Lopez Castells, advances the romantic and erotic theme that spills over almost all the fictions presented by Rubis. It is difficult to stop reading any of her stories. Not finishing any of them in a single seating is something that, unless we find ourselves obligated to do for circumstances we can’t control, we would not want to do. However, it is even more difficult to read two or more stories consecutively and without rest. It is that Rubis’ stories have the capacity to put the reader to work, making pause a necessity, to have to close the book, even for a short while. That way, as the book rests over the table waiting for the necessary calm that the turmoil of the last story demands, the time of reflection opens a door to a second look to the work of Lopez Castells. It is then when the initial softness of the painter’s palette opens way, awakened by the sensual indiscretions of Rubis’ characters, to the carnal aspect in the couple’s act, complementing and giving in that way, a more refined sense to selection of the book cover.

Any reader can understand and sympathize with such decision; nevertheless, this preamble is for me a tad limited, because it excludes the biblical heritage of these narratives. We, the ones that co-existed in the pastoral early stages of the author and that also attune our world’s vision in the tribunal of the believer’s altar, know that her Christian experiences from the beginning and, their historical and ideological substrates that accompanied them, are what sustain her stories. These tales are not really tales, but sermons, the logical continuation of the experience at the pulpit.

If the ministry is extended, this time it is done from a critical perspective of the role of organized religion in our society. The book makes this clear right from the outset. It is not only a master strike by a relatively unknown storyteller, at least at the time of the publication of “Cuentos Traidores”. The book begins with an exquisite, brief tale, as brief as only 7 sentences and like that, capture from the start with an inescapable hook the attention and interest of the reader; it also clarifies where the ex-religious minister, stands today with respect to those that profess the ministry. It is clear that the abandonment is limited to the institution, for the biblical stories that have nurtured millenary chimeras, continue being the well, from which Rubis extracts many of her stories. However, she makes it her responsibility to review the gospels in the context of a Jesus that is still the miracle maker, but in the role of creator of new realities, which to observing eyes are as incredible as healing the physically ill. Rubis breaches the distance to the true Jesus. The one that at the end of his bleak Lent, finally understands the character of his calling and embarks in his mission of unmasking all power, even if this means the sorrow of never realizing his desires of love with the Samaritan. The miracle occurs in the transformation of greed for charity, of lamentation and whining for gratitude for being alive, in short, a radical human change that is as unexpected as it is prodigious.

“That my word be the thing itself…” Juan Ramon Jimenez

Just like in the Bible, every verse and word of each passage ought to be minutely studied and pondered without desisting, if one is to uncover the occult meaning of the passage, capturing the treasure that each one of those contains, Rubis’ stories can be deconstructed as such passages. Fragments of observations, teachings, truths and the depths of the experience of being alive make up the story. However, each element taken individually also offers an inexhaustible source that reflects on and describes the significance of the human being. In preparation for this essay, during my second reading of the stories, I was pleasantly surprised by a series of sentences that again struck me after having “jamaqueado” my spirit in the first reading. The sentences were so well crafted, that as a naughty child, every once and then, I would add some of them to my Facebook page. I posted sentences on my wall; these were isolated and out of the story’s context. I just wanted to see the reactions of my friends. The experiment was well received as expected, for invariably while some would read and interpret them appropriately within the original context, even unbeknownst to them, others would find the most unexpected riches. Something similar to a preacher that uses a short biblical passage and within or without the appropriate context in which it was written as base, constructs a whole homily. The richness of the Rubis’ sentences provides sufficient material and inspiration for the creation of unexpected worlds. She, as creator of a thousand and one sentences that constitute her stories, is the obsessive mother who invested countless hours of sleeplessness in search for the precise order and word. At the beginning of my cyber experiment, Rubis could accurately identify whose character’s mouth had uttered the passage in a single glance. “Ujum, Luisa Capetillo”, she would guess correctly and with pride when read one of my first references. Unintentionally, my taste for Rubis’ decontextualized sentences began to become more refined; I orbited towards the most fetched and obscure ones. “Maria Antonieta?” Rubis wondered with certain doubt, facing the next quotation, “Hahaha” I have no idea. Enlighten me,” she confesses in the third round, disconcerted by the origin of her own words. I understood then how trances of prolific inspiration exist in which one can write beyond what one’s memory is capable of remembering.

Then, if within Rubis the Scriptural-Christian binomial seed germinated, evolving naturally with its origins in both universal mythology and literature, the transition toward the political realm could have not taken long. Embracing the icons of the Left, but much in her own way, Rubis, always different, recognizes the historical and political importance of these characters and introduces them with a detailed and thorough study of their inherent natures, intimate dreams, fears and hopes. Therefore, we have Don Pedro, who even while tortured by the colonial authorities is concerned about finding a successor to his continued preaching commitment. We see Ché Guevara, who even in the context of the African guerilla, suffers as he remembers his mother and reflects upon his childhood. We are introduced to Luisa Capetillo, who while imprisoned for seditious activities, ponders about her vivid recollection of the precise moment when, as a little girl, she decided to wear pants. Finally, we see a Santiago Iglesias Pantin, who becomes Capetillo’s confidante and in so doing, turns into container of her nostalgic writings.

After reading the book, I asked myself: What is my favorite story? I realize how hard it is to find an answer. In contrast to other collections of stories, this one contains none that is mediocre; all are complete and well executed in every respect. “Cuentos Traidores” is one of those books that I am proud to add to my personal library, as it meets a self-imposed condition at which I arrived on through the years. Pathological bibliomaniacs that we were, I would say after 15 or 20 years of continuous reading, we have to impose a limit to the initial irrational idea of storing every book of seeming potential or value. It’s a matter of space, and also budget. My criterion is the following: I will just buy or add to my library, books that deserve to be read several times. Books that with a single reading exhaust all potential and interest have no place on my bookshelves. “Cuentos Traidores” is a book well deserving of being read several times through the years. This quality implies, that like in any good book, the reader will continue to experience new emotions, interpretations and assessments with the passage of time. Therefore, to answer which stories I prefer would be relative to the time in which I answer. All this said and clarified, today perhaps the one I would have liked most is the story of Don Pedro and Jonah. However, because of its cleverness and its seal of fame, I had heard about this short story before reading it in its entirety. Moreover, although I fully enjoy reading it and I could still partake in the element of surprise to some extent for I did not know all its details; the speed and extent to which the information moves today robbed me of such delicious novelty. Then, I will choose two. The first is, without necessarily pretending preference, “Como de Plumas Malditas.” The exquisite crafting of the language and the delicious daring idea of bartering livers for penises, gives this ancient myth an enviable contemporaneousness to any writer of stories. The second, though, not secondary in any way, is “Dolores”. This is due to a pivotal event in the past two years, in which I’ve had the opportunity to become a father, even as I turned 52 years old. I have been granted the greatest blessing that existence has to offer. It is precisely because of this that I carry within me, with a most delicate sensibility, the message of this other favorite story. Since the recent 24 months, during which I have been sleeping next to my wife, I have noticed her breast-feeding our first child and now, doing the same with our second, I have been consumed by the warmth of family, along with the dreams and the invention of a future with the fruits of our own blood. Huddled on the bed our lives are now flooded with such tenderness and meaning. I would understand and share the experience of becoming fully unhinged like the mother in the story; facing the complete loss of connection with reality, if for some reason I were to undergo the implied loss and my dreams and longings were interrupted.

In this essay, my public reunion with the friend of my youth, is stamped with the placement of “Cuentos Traidores” on the first bookshelf of my library, fourth shelf, from left to right; a book I read as a private homage to Rubis. There it will stay, for my children and for me, along with José Luis Gonzalez, Luis Rafael Sanchez, Pedro Juan Soto, Rosario Ferré, Juan Antonio Ramos, Luis López Nieves, Rafael Acevedo, Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá, Luis Raúl Albaladejo, Magali García Ramis, Ana Lydia Vega, Jose M. Rodríguez Matos, Tomás López Ramírez, Manuel Ramos Otero, Edgardo Sanabria Santaliz, Manuel Abreu Adorno, Carmen Lugo Filippi, and many more other Puerto Rican literary giants of the last half century.

In the coming years I see myself visiting Rubis’ book on many occasions, the same way I do with the others, pleasantly influencing my thought and using it as an inexhaustible mine of dozens of epigraphs and references that inevitably will mold my future lines.

ReTURN

When we thought José had already used all possible proverbs born out of the fertile Puerto Rican imagination of the past century, he surprises us with a hundred other pages of popular islander wisdom in his second book of short stories, La Mancha Que Me Persigue (Palibrio, Bloomington, IN, 2011, ISBN: 978–1–4633–1323–4). It is almost as if the stories were written by themselves, giving the impression that all we have do is compile the one thousand and one idiomatic expressions of our insular Castilian, throw them randomly on a table and, in accordance to the order in which they fall, baste them together and observe how the stories build themselves. However, it would be a serious delusion to think it is so. These tales are made possible only by stepping into the shoes of this young man of Carolina. Thousands of stories seem to intertwine themselves in Jose’s memories when he confesses to his friends, those who live outside the book’s pages, that there are many more stories sprouting from the same source as the previous ones. It is in this inexhaustible narrative about our Puerto Rican nature that José makes us conscious of the “mancha,” the one that betrays us and reminds us who we are by keeping us face-to-face with it.

The morals of our native Aesop’s Fables, which if desired, could replace wolves and snakes from Mediterranean antiquity with cows and lizards of our spicy Caribbean, prefer using the characters of his people in the tales of José; that hidden crack of forest that opens between the mountains and the coast. Those memories and teachings, where proud men see the need to change haughtiness for humility, are what provide the necessary armor to face the troubled turbulent existence of exile and survival to which José alludes in the dedication of his book. Then we see how this armor comes undone, patch-by-patch, with these bits of memory. The weakness and defeat become so evident. It is listening to stories like those told by granny, during seductive nights, where the weak, rejected and forsaken one becomes the hero who finally triumphs over the giants who harass him. That is how we learned to be brave.

At the beginning, one gets the impression that the second group of stories could have been included in the first book, it would seem, that with the exception of the novelty of the characters, the themes, lessons and approaches it is fundamentally similar to the first volume. However, as we flip the pages and read the stories, we begin to perceive a new element, hidden in the fissures of the sentences, which, can be easily missed, unless one keeps eyes wide open.